The Foreman's Dilemma

Picture a construction site. A steel beam needs to be lifted to the second story. The site's crane is occupied, but a heavy-duty truck with a powerful 12,000-pound winch sits nearby. The thought is immediate and tempting: "Can't we just use the winch?"

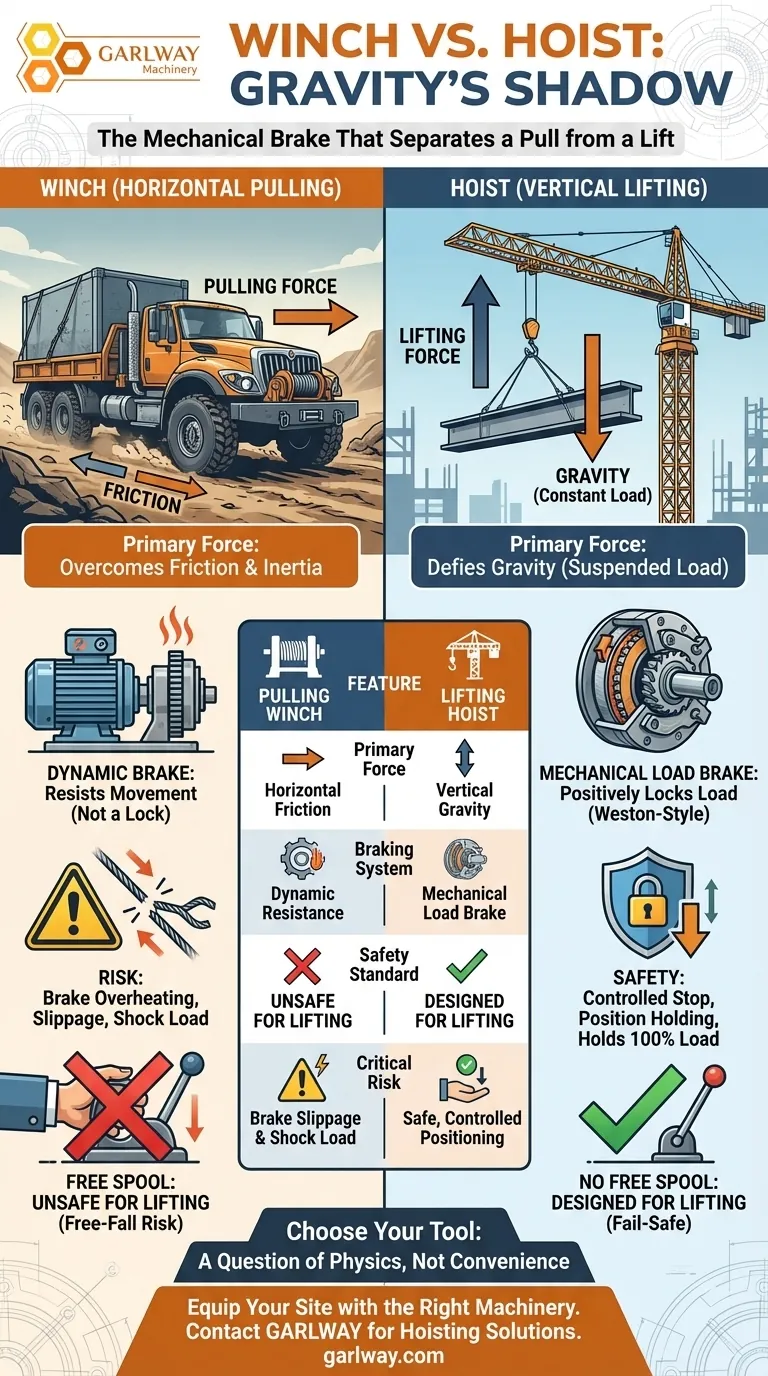

This question isn't born from negligence, but from a cognitive shortcut. Our brains see two machines that spool cable to move heavy objects and assume they are interchangeable. We see the obvious similarity in function and overlook the profound, invisible difference in physics.

The winch is designed to fight friction. The hoist is designed to fight gravity. Confusing the two is a gamble against fundamental forces.

The Psychology of Force: Pulling vs. Lifting

A standard winch's job is to pull a load horizontally. It overcomes the friction of the ground and the inertia of the object. While the forces are significant, they are variable and often aided by the object's ability to roll or slide.

A hoist does something far more absolute. It lifts a load vertically, taking on the full, relentless, and unforgiving force of gravity. There is no rolling resistance to help; there is only dead weight, suspended in the air, wanting to fall.

This distinction—pulling against friction versus lifting against gravity—is everything. It dictates an entirely different engineering philosophy, centered on one critical component: the brake.

The Heart of the Machine: The Braking System

The core difference between a winch and a hoist isn't its motor or its rope. It's in how it fails. The brake determines whether a failure is a controlled stop or a catastrophe.

The Winch's Dynamic Brake

A standard pulling winch uses a dynamic braking system. This brake relies on the resistance within the electric motor and the gear train to hold the line. Think of it like downshifting a manual car to slow down on a hill. It provides resistance, but it’s not a positive lock. It was never intended to hold a suspended load against the full, constant pull of gravity.

The Hoist's Mechanical Brake

A hoist, or a winch specifically rated for lifting, uses a mechanical load brake. This is a physically locking brake, often a Weston-style system, that automatically engages the instant the lifting stops. It doesn't just resist movement; it physically prevents the drum from turning. It is designed to hold 100% of the rated load, even if the power cuts out. It is the engineering equivalent of a promise: this load will not fall.

The Anatomy of a Failure

Using a standard winch for a vertical lift doesn't just introduce risk; it creates a predictable sequence of failure.

1. The Inevitability of Slippage

Under the constant strain of a suspended load, a dynamic brake will generate immense heat. As it overheats, it begins to slip. At first, it might be imperceptible, but gravity is patient. The slip will worsen until the brake can no longer hold.

2. The Danger of Shock Loading

When a slipping load drops even a few inches and the brake momentarily catches, it creates a shock load. The instantaneous force on the rope, gears, and mounting points can be several times the actual weight of the object. This is how a 1,000-pound load can snap a 5,000-pound cable.

3. The Unforgivable Flaw: The Free Spool

Many pulling winches have a clutch or "free spool" feature, allowing a user to quickly pull the rope out by hand. In a lifting scenario, this is an exposed trigger. An accidental engagement would instantly disconnect the gear train, causing the suspended load to free-fall.

Choosing Your Tool: A Question of Physics, Not Convenience

The choice between a winch and a hoist is not a matter of preference. It is a mandate dictated by the task.

- For horizontal pulling, like vehicle recovery or dragging materials across the ground, a standard winch is the correct, efficient tool.

- For vertical lifting, like hoisting engines, building materials, or any suspended load, you must use a device with a mechanical load brake. This means a chain hoist, an electric hoist, or a winch explicitly designed and rated for hoisting.

The table below clarifies the non-negotiable differences:

| Feature | Standard Pulling Winch | Lifting Hoist / Hoisting Winch |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Force | Overcomes Friction (Horizontal) | Defies Gravity (Vertical) |

| Braking System | Dynamic (Resists Movement) | Mechanical Load Brake (Locks Load) |

| Safety Standard | Unsafe for Lifting | Designed for Lifting |

| Critical Risk | Brake Overheating, Slippage, Shock Load | Safe, controlled positioning |

On any professional construction site, from large-scale commercial projects to specialized contracting, understanding this distinction is fundamental to safety and efficiency. Equipping your team with machinery designed for the specific forces they will encounter is not just best practice—it's the only way to operate.

For construction projects that demand uncompromising safety and efficiency, ensuring your equipment is rated for the specific task is paramount. Contact Our Experts to equip your site with the right machinery for the job.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Small Electric Winch 120V and 240V for Compact Applications

- Portable Small Trailer Winch

- Electric 120V Boat Winch by Badlands

- Quick Windlass Portable Winch for Truck and Boat Best Boat Winch

- Electric and Hydraulic Winch for Heavy Duty Applications

Related Articles

- How Wire Rope Mechanics Dictate Winch Drum Design for Optimal Performance

- The Unseen Force: Why Your Winch's Amperage is the System's Weakest Link

- How Electric Winches Prevent Damage in High-Value Material Handling

- The Unseen Engine: How a Winch Converts Power into Progress

- The Single Point of Failure: Why a Winch Is Not a Hoist