At its core, the design principle of a windlass is the conversion of rotational motion into a powerful linear pull. It uses the mechanical advantage of a wheel and axle system, often enhanced by gears, to multiply a small input force—like turning a crank—into a much larger force capable of lifting heavy loads like a ship's anchor.

The fundamental principle is trading distance for force. By applying a small force over a long rotational distance (turning a handle many times), the windlass generates a large pulling force over a short linear distance (lifting the load slowly).

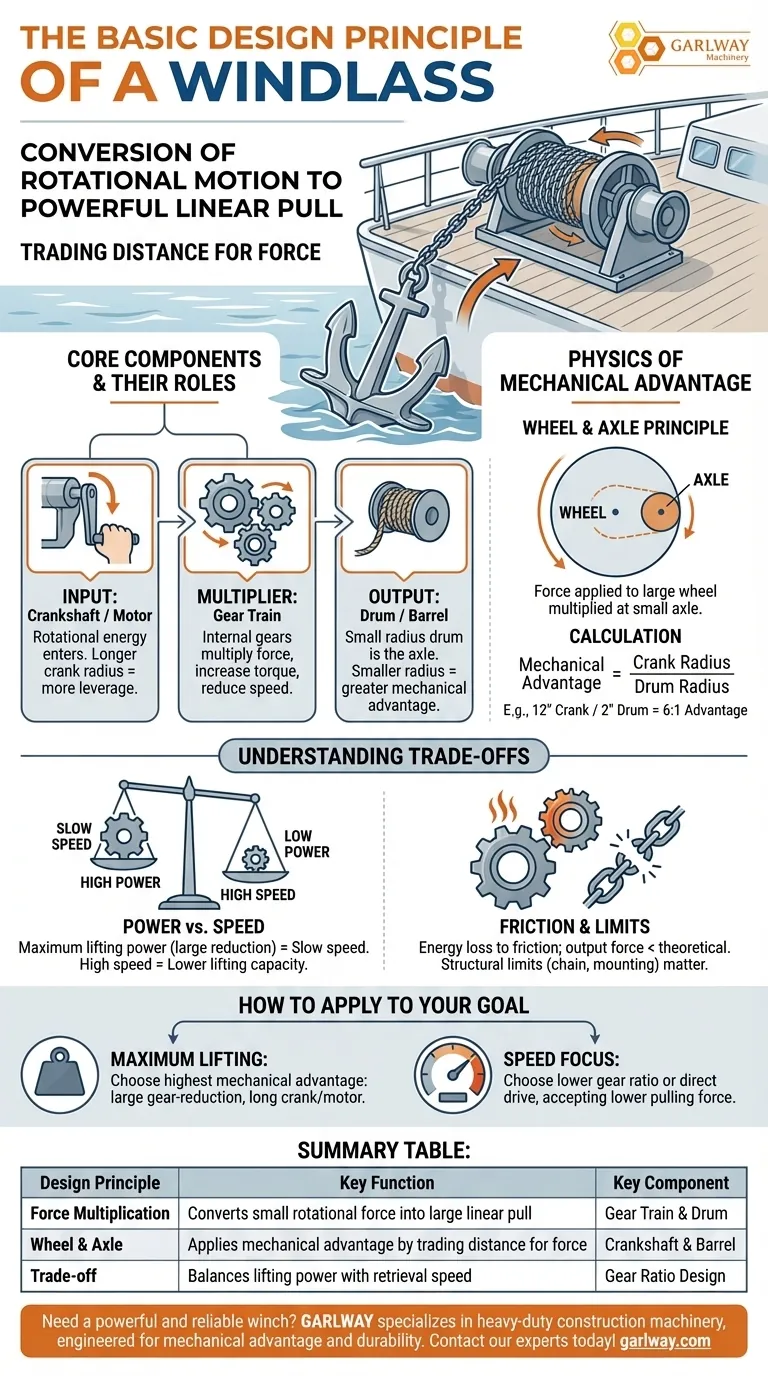

The Core Components and Their Roles

A windlass is a simple machine, but its effectiveness comes from how its parts work together to create mechanical advantage. Understanding each component reveals how the force is multiplied.

The Input: Crankshaft or Motor

This is where energy enters the system. A user turns a crank or a motor provides rotational power. The key factor here is the radius of the turn; a longer crank handle provides more leverage.

The Multiplier: The Gear Train

While not always visible, most modern windlasses use internal gears. A small gear driven by the motor or crank turns a much larger gear connected to the drum. This gear reduction is the primary source of force multiplication, dramatically increasing torque while reducing speed.

The Output: The Drum or Barrel

This is the axle of the system. The rope, cable, or anchor chain wraps around this central barrel. Its small radius is critical; the smaller the drum's radius compared to the radius of the crank or the effective radius of the gearing, the greater the mechanical advantage.

The Physics of Mechanical Advantage

The "magic" of a windlass isn't magic at all—it's a direct application of fundamental physics. It's a classic example of a simple machine known as the wheel and axle.

The Wheel and Axle Principle

Think of the crank's path as a large "wheel" and the drum as the "axle." Force applied to the edge of the large wheel is multiplied at the surface of the smaller axle. This simple relationship is the foundation of the windlass's power.

Trading Distance for Force

There is no such thing as free energy. The advantage gained in force must be paid for with distance. To lift an anchor one foot, you may need to turn the crank handle through a circular path of 30 feet. This trade-off is what makes the task possible for a human or a small motor.

Calculating the Advantage

The theoretical mechanical advantage is the ratio of the radius of the crank's rotation to the radius of the drum. A 12-inch crank handle turning a 2-inch radius drum provides a 6:1 advantage, even before considering any gears.

Understanding the Trade-offs

No mechanical system is perfect. The design of a windlass is governed by a primary trade-off and is subject to real-world limitations.

Power vs. Speed

This is the most critical trade-off. A windlass designed for maximum lifting power, with a large gear reduction, will be very slow. Conversely, a windlass designed for high-speed retrieval will have a much lower lifting capacity.

The Impact of Friction

Energy is always lost to friction within the gears and bearings of the windlass. This means the actual output force is always slightly less than the theoretical calculated force. Well-maintained and properly lubricated components minimize this loss.

Material and Structural Limits

The mechanical advantage is useless if the machine itself cannot withstand the forces involved. The strength of the chain, the drum's integrity, and the security of its mounting to the deck are all critical limiting factors.

How to Apply This to Your Goal

Understanding the core principle allows you to evaluate a windlass based on its intended purpose.

- If your primary focus is lifting maximum weight: You need a design with the highest possible mechanical advantage, which means a large gear-reduction ratio and a long crank or powerful motor.

- If your primary focus is speed: You should choose a system with a lower gear ratio or even a direct drive, understanding that this will limit its maximum pulling force.

Ultimately, the simple principle of converting a long, easy rotation into a short, powerful pull is what allows a windlass to perform monumental work with minimal effort.

Summary Table:

| Design Principle | Key Function | Key Component |

|---|---|---|

| Force Multiplication | Converts small rotational force into large linear pull | Gear Train & Drum |

| Wheel & Axle | Applies mechanical advantage by trading distance for force | Crankshaft & Barrel |

| Trade-off | Balances lifting power with retrieval speed | Gear Ratio Design |

Need a powerful and reliable winch for your construction or marine project? GARLWAY specializes in heavy-duty construction machinery, including winches, concrete mixers, and batching plants. Our equipment is engineered for maximum mechanical advantage and durability, helping construction companies and contractors globally handle heavy loads with ease. Contact our experts today to find the perfect winch solution for your specific needs!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Heavy Duty Electric Boat Winch Windlass Anchor

- Warn Winch Windlass Boat Trailer Winch

- Electric Hoist Winch Boat Anchor Windlass for Marine Applications

- Ready Mixer Machine for Construction Ready Mix Machinery

- Portable Cement Mixer with Lift Concrete Machine

People Also Ask

- What are winch bars used for? Essential Tool for Safe Cargo Securement

- How does the size of a winch influence the diameter of its drum? A Guide to Load Capacity & Speed

- What role does a winch play in tackling steep inclines? Achieve Safe, Controlled Ascents with GARLWAY

- What are the main components of a winch? Unlock the Power of Pulling Technology

- What is the primary function of a hoist in industrial applications? Lift, Lower, and Transport Heavy Loads Efficiently

- What makes electric winches versatile for different lifting applications? Achieve Superior Adaptability for Your Projects

- What is the function of the motor and gearbox in an electric winch? Powering Your Heavy-Duty Pulls

- How is the drum constructed in an electric winch? The Heart of Pulling Power Explained