In construction, a deep foundation is used when the soil near the surface is too weak to support the structure's weight. It serves as a necessary solution when site constraints or exceptional structural loads make a conventional shallow foundation impossible or unsafe.

A deep foundation is not just a bigger version of a shallow one; it is a fundamentally different strategy. Instead of relying on the surface soil, it acts as a structural bridge, transferring the building's weight through weak layers to reach competent, load-bearing strata far below.

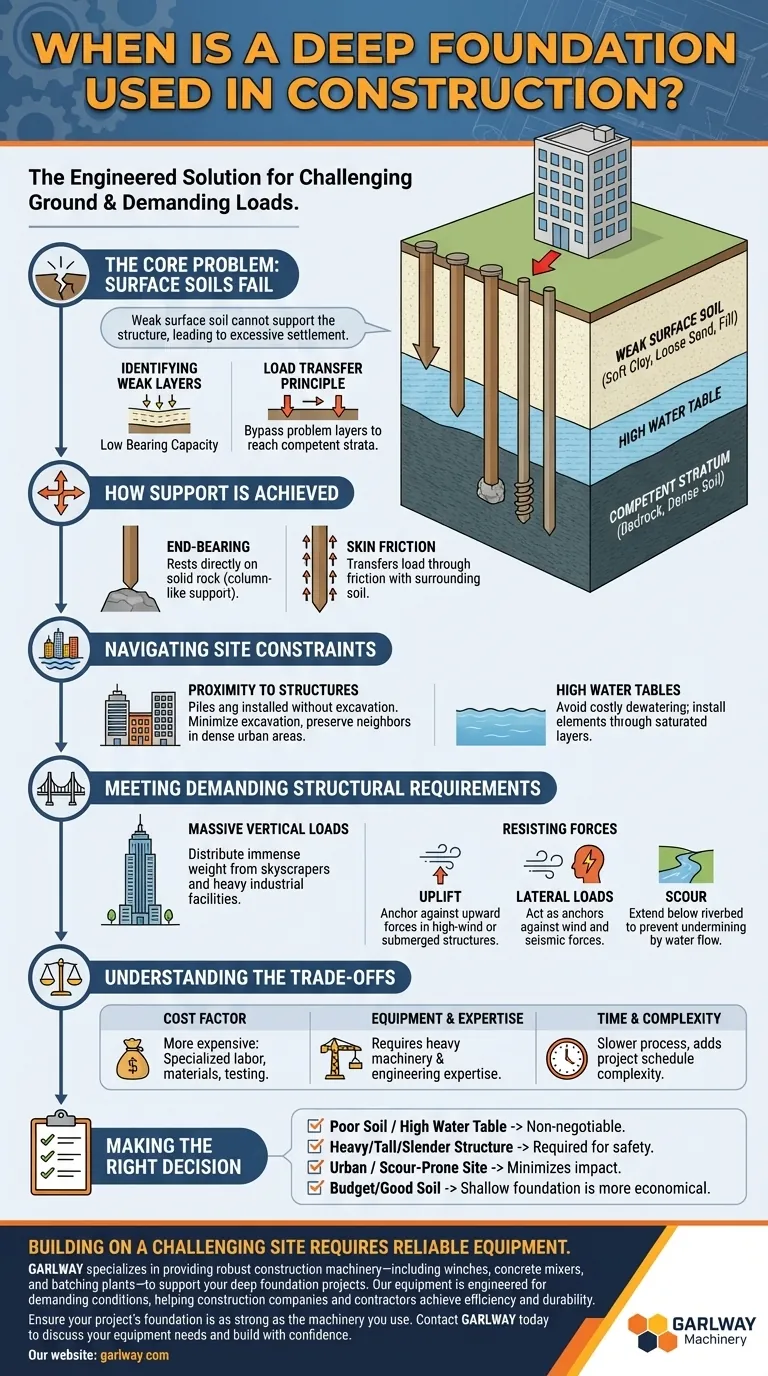

The Core Problem: When Surface Soils Fail

The decision to use a deep foundation almost always begins with a geotechnical investigation that reveals inadequate soil conditions near the surface.

Identifying Weak Upper Soil Layers

Weak soils have a low bearing capacity, meaning they compress or shear easily under load. This can include loose sands, soft clays, or improperly compacted fill material. Building on such ground with a shallow foundation would lead to excessive and uneven settlement, causing severe structural damage.

The Principle of Load Transfer

A deep foundation works by bypassing these problematic upper layers entirely. Elements like piles or piers are driven or drilled deep into the ground until they reach a layer of rock or very dense soil with adequate bearing capacity. The building's load is then transferred directly to this competent stratum.

How Deep Foundations Achieve Support

Support is achieved in two primary ways. End-bearing is when the pile acts like a column, resting directly on solid rock. Skin friction is when the pile transfers the load to the surrounding soil along its entire length through friction. Most deep foundations utilize a combination of both.

Navigating Difficult Site Constraints

Sometimes the soil itself is adequate, but the surrounding environment makes a standard shallow foundation impractical.

Proximity to Existing Structures

In dense urban areas, excavating for a wide shallow foundation can undermine the foundations of adjacent buildings, risking their stability. Deep foundations, such as drilled piers or driven piles, can be installed with minimal excavation, preserving the integrity of neighboring structures.

High Water Tables

Digging a large, open pit for a shallow foundation below the water table requires extensive and costly dewatering operations. Deep foundation elements can be installed through water-saturated layers of soil much more efficiently, avoiding the need to pump out massive quantities of groundwater.

Meeting Demanding Structural Requirements

Certain structures have loads that are simply too great for even good-quality surface soils to handle.

Supporting Massive Vertical Loads

Skyscrapers, heavy industrial facilities, and long-span bridges concentrate enormous weight onto relatively small footprints. A deep foundation system distributes this immense vertical load safely to deeper, stronger layers of the earth.

Resisting Uplift and Lateral Forces

Deep foundations are not just for pushing down. They are critical for resisting other forces.

- Uplift: Tall structures in high-wind areas or structures built below the water table need to be anchored against upward forces.

- Lateral Loads: Forces from wind, earthquakes, or retained soil push structures sideways. Deep foundations act like buried anchors, providing the necessary lateral stability.

- Scour: Bridge piers in rivers must have foundations that extend deep below the riverbed, beyond the depth where rushing water can wash away (scour) the surrounding soil.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing a deep foundation is a decision driven by necessity, not preference, primarily due to its significant trade-offs.

The Cost Factor

Deep foundation systems are substantially more expensive than shallow foundations. The costs include specialized labor, geotechnical consulting, material costs for steel or concrete piles, and extensive quality control testing.

Specialized Equipment and Expertise

Installing deep foundations requires heavy, specialized machinery like pile drivers and large-diameter drill rigs. The design and installation process demands a high level of expertise from both geotechnical and structural engineers.

Time and Project Complexity

The process is typically slower than building a shallow foundation. It adds complexity to the project schedule, including time for pile load testing to verify capacity and integrity.

Making the Right Geotechnical Decision

The final choice hinges on a careful analysis of the soil conditions, the structural demands, and the project constraints.

- If your site has poor soil conditions or a high water table: A deep foundation is likely non-negotiable to ensure long-term stability and bypass problematic ground.

- If your structure is exceptionally heavy, tall, or slender: A deep foundation system is required to safely manage immense vertical loads and resist lateral forces like wind or seismic activity.

- If you are building in a constrained urban environment or a scour-prone area: Deep foundations provide a solution that minimizes impact on adjacent properties and protects against environmental forces.

- If your budget is the primary driver and the site has good soil: A shallow foundation is almost always the more economical and straightforward choice.

Ultimately, the choice is dictated by the ground itself; a deep foundation is the engineered response when the earth's surface simply cannot provide the necessary support.

Summary Table:

| Scenario | Reason for Deep Foundation | Foundation Type Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Surface Soil | Bypass low-bearing capacity layers (soft clay, loose sand) | Driven Piles, Drilled Piers |

| High Structural Loads | Support skyscrapers, heavy industrial facilities | End-bearing Piles, Friction Piles |

| Constrained Urban Sites | Minimize excavation and protect adjacent buildings | Micropiles, Secant Piles |

| High Water Table / Scour Risk | Avoid dewatering; anchor below erosion depth | Caissons, Drilled Shafts |

| Lateral/Uplift Forces | Resist wind, seismic activity, or buoyancy | Battered Piles, Anchored Piles |

Building on a challenging site requires reliable equipment.

GARLWAY specializes in providing robust construction machinery—including winches, concrete mixers, and batching plants—to support your deep foundation projects. Our equipment is engineered for demanding conditions, helping construction companies and contractors achieve efficiency and durability.

Ensure your project's foundation is as strong as the machinery you use. Contact GARLWAY today to discuss your equipment needs and build with confidence.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- HZS35 Small Cement Concrete Mixing Batch Plant

- JW1000 Mobile Cement Mixer Concrete Mixer Truck and Batching Plant

- HZS180 Ready Mix Concrete Plant for Foundations with Sand and Cement

- HZS120 Ready Mix Concrete Batching Plant Commercial Mud Cement Mixer

- Shaft Mixer Machine for Cement and Regular Concrete Mixing

People Also Ask

- What are some alternative uses for winches beyond vehicle recovery? Boost Your Productivity on Land, Job Sites, and Farms

- What is the most critical factor in concrete quality control? Master the Water-to-Cement Ratio

- What safety measures should be identified before hoist operation? A 3-Pillar Checklist for a Safe Lift

- What are the primary uses of mortar in construction? A Guide to Durable Masonry

- What are the components of a jib crane? A Guide to Core Lifting System Parts

- How does a mixing machine work? A Guide to Blending Audio Signals Perfectly

- What is the function of the gear train in a towing winch? Unlocking the Power for Heavy-Duty Recovery

- What is the duty-cycle capability of full-on hydraulic winches? Achieve Non-Stop Pulling Power for Demanding Jobs