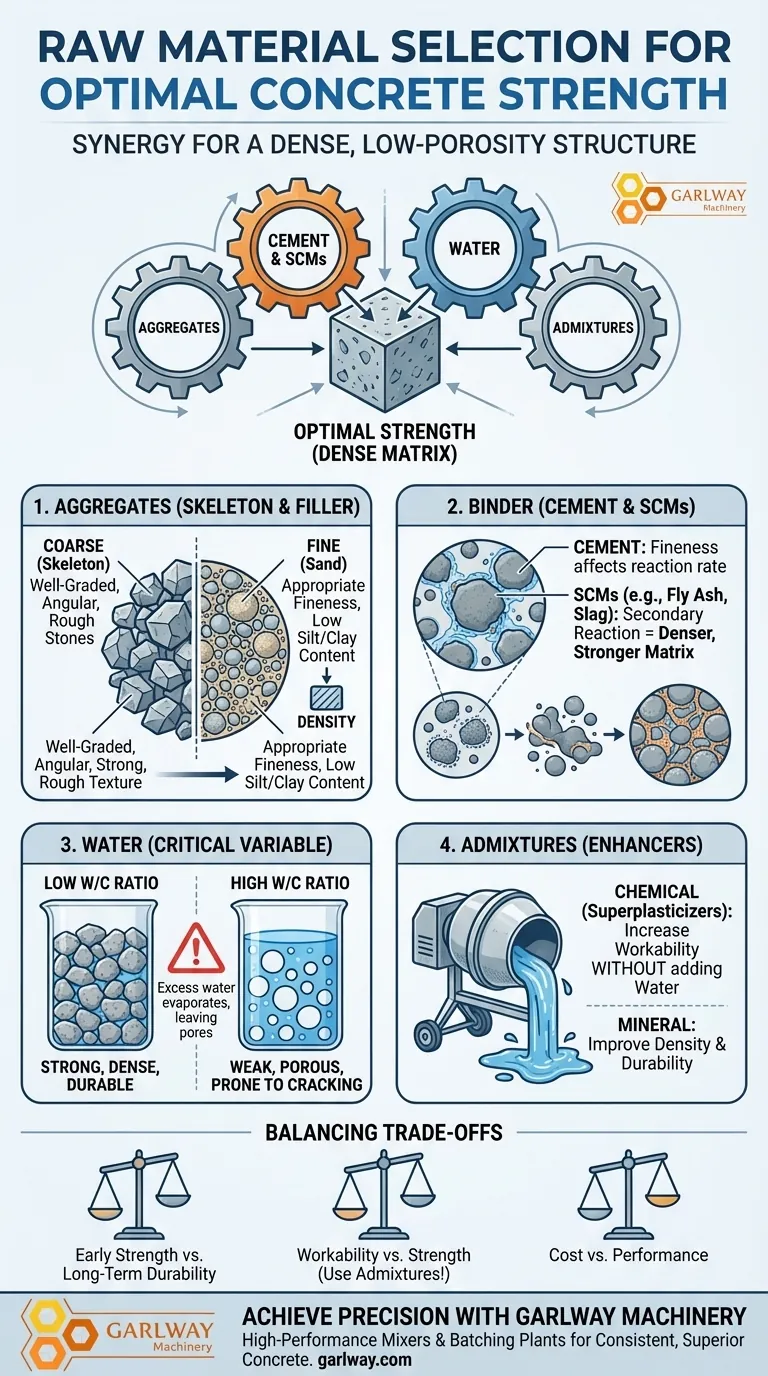

To ensure optimal concrete strength, your selection process must meticulously evaluate every core component: aggregates, cement, water, and any admixtures. The ideal material for each is not an absolute but is determined by its interaction with the others, with the primary goals being to create a dense, well-bonded internal structure and to minimize porosity.

The ultimate strength of concrete is not determined by a single "best" ingredient, but by the strategic synergy of its raw materials. The most critical factor is the precise control of the water-to-cement ratio, as excess water directly creates weakness.

The Foundation: Aggregates (Coarse and Fine)

Aggregates form the bulk of the concrete volume (60-75%), acting as its structural skeleton. Their physical properties are the first line of defense in achieving high strength.

Coarse Aggregates: The Concrete's Skeleton

The size, shape, and composition of your coarse aggregate (like gravel or crushed stone) are fundamental.

Gradation, or the distribution of different particle sizes, is paramount. A well-graded aggregate mix, with a range of sizes, allows smaller particles to fill the voids between larger ones, creating a densely packed and stronger final product.

Morphology, or the shape and texture of the aggregate, influences the bond with the cement paste. Angular, rough-textured crushed stone creates a stronger mechanical interlock than smooth, rounded river gravel.

Finally, the intrinsic strength of the aggregate material itself must be higher than the target strength of the concrete. A weak aggregate will fracture before the cement paste fails, creating a ceiling for potential strength.

Fine Aggregates (Sand): Filling the Voids

Sand fills the smaller voids between the coarse aggregates, further increasing density.

The fineness modulus indicates the average size of the sand particles. An appropriate fineness ensures the mix is workable without demanding excess water, which would compromise strength.

Critically, the sand must have very low mud or silt content. These fine contaminants interfere with the bond between the cement paste and the aggregates, creating weak points within the concrete matrix.

The Binder: Cement and Supplementary Materials

This paste coats the aggregates and binds them together through a chemical reaction known as hydration.

Cement: The Engine of Strength

Cement provides the chemical reaction that gives concrete its strength.

The fineness of the cement particles (measured as specific surface area) affects the rate of this reaction. Finer cement hydrates faster, leading to higher early strength, but coarser cement can contribute to better strength development over the long term and generate less heat during curing.

Mineral Admixtures: The Strength Enhancer

Materials like slag powder or fly ash are not just fillers; they are supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs).

When used to replace a portion of the cement, these materials participate in a secondary chemical reaction. This creates additional calcium-silicate-hydrate (C-S-H), the primary binding compound in concrete, resulting in a denser, less permeable, and ultimately stronger and more durable matrix over time.

The Critical Variable: Water Content

While essential for the chemical reaction, water is also the most common source of weakness in concrete.

The Water-Cement Ratio: The Golden Rule

The strength of concrete is inversely proportional to its water-to-cement (w/c) ratio.

Water is required for hydration, but any water added beyond what is needed for this reaction will remain in the mix. As the concrete hardens, this excess water evaporates, leaving behind a network of pores that directly reduces the final compressive strength and durability.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Selecting materials is an exercise in balancing competing factors. There is no single "perfect" mix for all applications.

Early Strength vs. Long-Term Durability

Using a very fine cement can provide the high early strength needed for rapid construction schedules. However, this can generate significant heat, increasing the risk of thermal cracking, and may not achieve the same ultimate strength as a mix with SCMs designed for long-term performance.

Workability vs. Strength

The easiest way to make concrete flow better is to add more water, but this is the fastest way to compromise its design strength. The correct approach is to use chemical admixtures, like superplasticizers, which increase fluidity without altering the critical water-cement ratio.

Cost vs. Performance

Sourcing perfectly graded, high-strength aggregates and using specialized admixtures increases material costs. The goal is always to select a combination of materials that meets the specific engineering requirements for strength and durability in the most economical way possible.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your material selection should be guided by the primary performance requirement of the concrete.

- If your primary focus is maximum compressive strength: Prioritize a very low water-cement ratio, use well-graded and angular high-strength coarse aggregates, and consider mineral admixtures like silica fume.

- If your primary focus is early strength for rapid construction: Select a finer cement or use a strength-accelerating chemical admixture, while maintaining strict control over the water content.

- If your primary focus is long-term durability and chemical resistance: Incorporate supplementary cementitious materials like slag or fly ash and use a properly graded, non-reactive aggregate.

Ultimately, designing for strength is about creating a dense, optimized system where every material works in concert to minimize voids and maximize bond.

Summary Table:

| Material | Key Selection Criteria for Optimal Strength |

|---|---|

| Coarse Aggregates | Well-graded mix, angular shape, rough texture, high intrinsic strength |

| Fine Aggregates (Sand) | Appropriate fineness modulus, very low silt/clay content |

| Cement | Suitable fineness for desired strength development (early vs. long-term) |

| Water | Strict control of water-cement (w/c) ratio; excess water creates weakness |

| Admixtures | Use superplasticizers for workability; mineral admixtures (e.g., fly ash) for denser matrix |

Achieve Unmatched Concrete Strength with GARLWAY

Building durable, high-strength structures requires precision-engineered materials and equipment. GARLWAY specializes in providing construction companies and contractors worldwide with the reliable machinery needed to produce superior concrete on-site.

We empower your projects with:

- High-Performance Concrete Mixers: Ensure a consistent, homogenous mix for optimal material synergy and strength.

- Efficient Concrete Batching Plants: Precisely control the proportions of aggregates, cement, and water for the perfect mix every time.

Let's build stronger together. Contact our experts today to discuss how our concrete machinery solutions can be tailored to meet the specific strength and durability requirements of your next project.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- HZS35 Small Cement Concrete Mixing Batch Plant

- HZS180 Ready Mix Concrete Plant for Foundations with Sand and Cement

- HZS75 Concrete Batching Plant Cement Mixer Price Concrete Mixer Bunnings Mixing Plant

- HZS120 Ready Mix Concrete Batching Plant Commercial Mud Cement Mixer

- JW1000 Mobile Cement Mixer Concrete Mixer Truck and Batching Plant

People Also Ask

- What is travel speed in electric hoists? A Key Factor for Efficient & Safe Load Handling

- How does vehicle size affect winch usage? Choose the Right Winch for Your Truck's Weight

- What additional equipment is often needed alongside winch machines for mooring operations? A Guide to the Complete System

- Why should personnel stay clear of a suspended load? Prevent Catastrophic Injury or Death

- How is a winch used for 4x4 vehicles? A Guide to Off-Road Self-Recovery

- How does a winch convert energy into pulling power? Master the Mechanics for Maximum Force

- What are the best practices for managing hydraulic oil in winches? Ensure Maximum Reliability and Longevity

- What types of cable release systems do hydraulic winches have? Choose Between Mechanical or Pneumatic