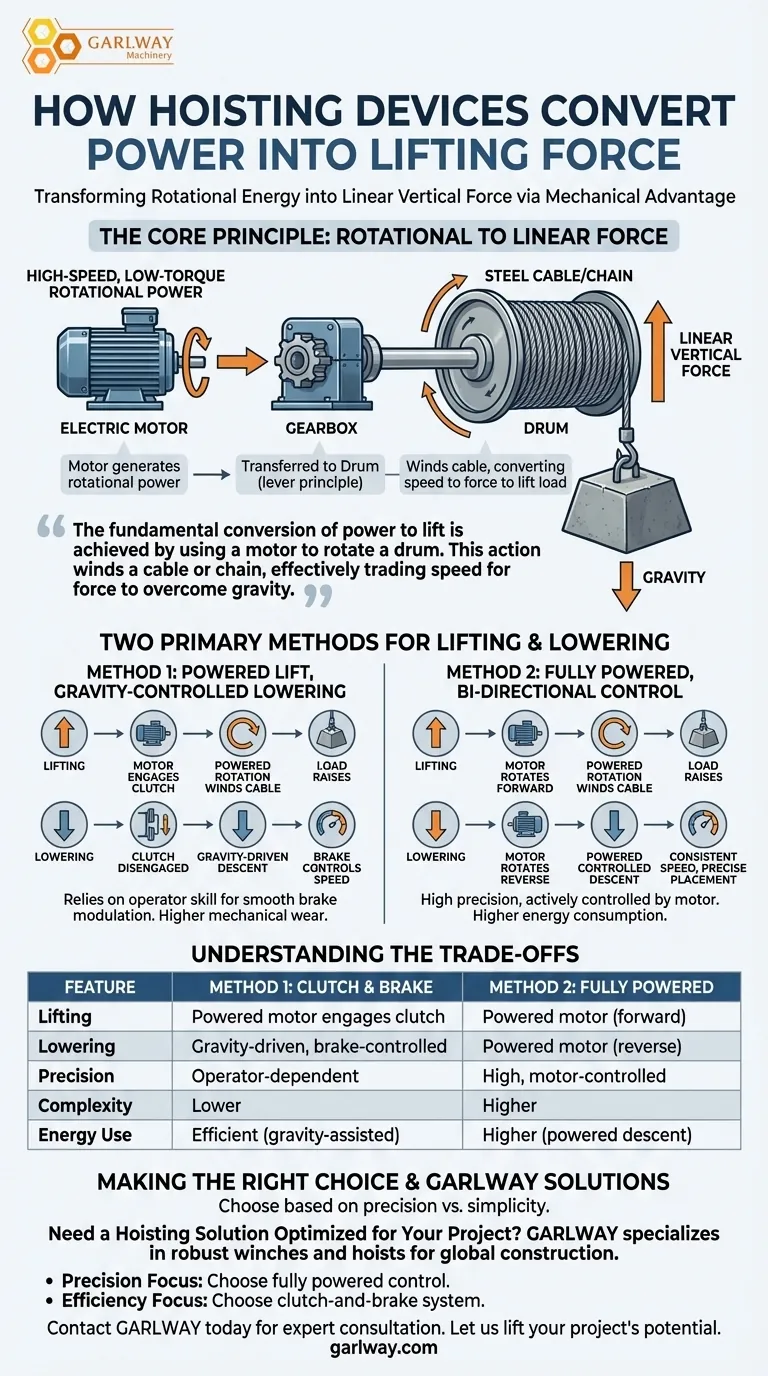

At its core, a hoisting device transforms rotational energy into linear vertical force through mechanical advantage. It uses a power source, typically an electric motor, to turn a drum or winch. This rotation winds a rope or chain, converting the motor's high-speed, low-force output into the low-speed, high-force action required to lift a heavy load, much like a simple lever.

The fundamental conversion of power to lift is achieved by using a motor to rotate a drum. This action winds a cable or chain, effectively trading speed for force to overcome gravity and lift an object.

The Core Principle: Rotational to Linear Force

A hoist is a system designed to create significant mechanical advantage. It doesn't create energy, but rather converts it into a more useful form for lifting.

The Motor as the Power Source

The process begins with a motor, which generates rotational power. This power is characterized by high speed but relatively low torque—insufficient on its own to lift heavy objects.

The Drum as a Rotational Lever

The motor's rotation is transferred, often through a gearbox, to a central component called a drum. As the drum rotates, it spools a rope or chain onto its surface.

This action is analogous to the lever principle. The radius of the drum acts as a lever arm, converting the rotational force (torque) from the motor into a powerful linear pulling force on the cable, which then lifts the load.

Two Primary Methods for Lifting and Lowering

While the lifting principle is consistent, how a hoist controls the lowering of a load typically falls into one of two distinct mechanical designs.

Method 1: Powered Lift, Gravity-Controlled Lowering

This is a very common design for many types of hoists and winches.

During the lifting phase, a clutch connects the motor to the drum, allowing the powered rotation to wind the cable and raise the load.

To lower the load, the clutch is disengaged. This disconnects the motor from the drum. The load's own weight (gravity) causes the drum to reverse and unwind the cable. The speed of this descent is managed entirely by a brake, which applies friction to prevent an uncontrolled drop.

Method 2: Fully Powered, Bi-Directional Control

In this second type of hoist, the motor remains engaged for both lifting and lowering. There is no clutch to disengage.

Lifting is achieved when the motor rotates in its forward direction.

To lower the load, the motor's direction of rotation is simply reversed. This provides a powered, controlled descent at a consistent speed, offering precise placement without relying on gravity and a brake for speed control.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The choice between these two control mechanisms has direct implications for performance, complexity, and safety.

Precision vs. Simplicity

The fully powered, bi-directional method offers far greater precision during lowering, as the speed is actively controlled by the motor. The gravity-controlled method is mechanically simpler but relies on the skill of the operator to smoothly modulate the brake.

Component Wear

The clutch-and-brake system introduces more mechanical wear points. The clutch must engage and disengage repeatedly, and the brake pads are consumed over time by friction, requiring regular inspection and replacement.

Energy Consumption

A gravity-controlled descent is highly energy-efficient, as it uses the load's potential energy to do the work. A powered descent consumes energy to drive the motor in reverse, although it offers superior control in return.

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Understanding these core designs helps you evaluate the right tool for a specific task.

- If your primary focus is precision and controlled placement: A hoist with fully powered, bi-directional motor control is the superior choice.

- If your primary focus is simple load movement and energy efficiency: A system using the clutch-and-brake method for gravity-assisted lowering is often sufficient and effective.

By recognizing how a hoist converts power and controls a load, you can operate the equipment with greater safety and efficiency.

Summary Table:

| Feature | Method 1: Clutch & Brake | Method 2: Fully Powered |

|---|---|---|

| Lifting | Powered motor engages clutch | Powered motor (forward) |

| Lowering | Gravity-driven, brake-controlled | Powered motor (reverse) |

| Precision | Operator-dependent | High, motor-controlled |

| Complexity | Lower | Higher |

| Energy Use | Efficient (gravity-assisted) | Higher (powered descent) |

Need a Hoisting Solution Optimized for Your Project?

Understanding the mechanics is the first step. Choosing the right equipment is what ensures safety, efficiency, and precision on your job site. GARLWAY specializes in engineering robust construction machinery, including winches and hoists, for construction companies and contractors globally.

We can help you select the perfect hoist—whether you need the precision of fully powered control or the efficiency of a clutch-and-brake system—to enhance your operational safety and productivity.

Contact GARLWAY today for a expert consultation and let us lift your project's potential.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electric Hoist Winch Boat Anchor Windlass for Marine Applications

- Ready Mixer Machine for Construction Ready Mix Machinery

- Commercial Construction Mixer Machine for Soil Cement Mixing Concrete

- Auto Concrete Cement Mixer Machine New

- Portable Electric Small Cement Mixer Concrete Machine

People Also Ask

- What is an industrial winch? The Essential Guide to Safe Heavy Load Pulling

- What are the pros of using a synthetic rope for a winch? Discover the Key Benefits for Safety and Performance

- What are the rated speeds of slow-speed and high-speed winches? A Guide to Choosing for Control or Efficiency

- What maintenance should be performed on the windlass? A Proactive Guide to Reliability

- What are the main benefits of electric winches compared to hydraulic ones? Discover Simpler, More Cost-Effective Lifting

- Why is transmission type important when selecting a lubricant for the deceleration device of a building electric hoist? Ensure Optimal Performance & Safety

- What features make a winch reliable and convenient for truck owners? Ensure Safe, Powerful Recovery

- How can a winch be powered on a trailer? A guide to choosing the right setup for your needs.